The Choral Warm-Ups of Robert Shaw

by Pam Elrod Huffman with edits by John Cooledge

Noted choral conductor Robert Shaw regarded the often-slighted chorus warm-up as an absolutely essential part of every rehearsal. His use of it, focusing on unification of tuning, tone color, ensemble blend, and development of dynamic range clearly demonstrated Shaw’s extraordinary creativity. For many conductors, the warm-up period—when used at all—is simply a time for vocalizing the singers. With Shaw, the warm-up was something else entirely. He did not consider his role to be that of a studio voice instructor leading his forces through an array of vocal exercises. Each singer was expected to vocalize independently prior to rehearsal, so that the warm-up time could be used to "tune" the ears and the brain. It was during this brief portion of his rehearsals that he began to instill in his singers the art of being an ensemble. For Shaw, this was a time to establish disciplines crucial to the ensemble's maturing into a truly expressive musical instrument.

Making Warm-Ups Relevant

Shaw's warm-ups were effective because of their pedagogical soundness and relevance to the rehearsal process. They are an integral part of all of this writer’s rehearsals, regardless of age level of the singers, though with student singers warm-ups sometimes do need to cover basic matters such as breathing and vocalization in addition to exercises such as Shaw utilized. From beginning to end, the warm-up process can take roughly ten minutes—but those are often the most important ten minutes of the rehearsal.

The following are exercises Shaw used, notated and with audio examples. They are listed roughly in the order in which he would use them—although he would never have employed all of them in a single warm-up. Instead, Shaw would choose among them for relevance to the rehearsal (or performance) at hand, taking into consideration repertoire, acoustical issues, and the ensemble itself. He constantly "tweaked" the exercises, altering them to fit the needs of the occasion, with a side benefit of keeping the singers from settling too much into routine.

The Warm-Up Exercises

In order to produce the purest possible sound, Shaw asked the chorus to sing all of these exercises substantially without vibrato. On open vowels this practice will generate clearly audible overtones when singers achieve finely tuned intonation: in a mixed chorus the most evident overtone will lie a perfect fifth above the treble voices. Shaw maintained that immaculate vibrato-free tuning and its resulting overtones can lead to a more sonorous and vital sound. In theory, a smaller chorus can generate a bigger sound than a larger ensemble which doesn’t use these principles of unification. .

For each of the following exercises a beginning pitch is suggested, but you may start with a higher or lower pitch depending on the needs of your group. (Exercise 7 is the only possible exception—the pitches indicated seem to be the most suitable, given the extremes of vocal range that are required).

Vowel Unification

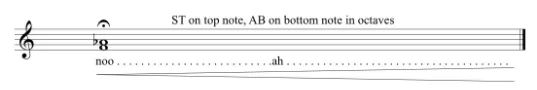

1. Use a single pitch, in unison (or octaves) on the nonsense syllable, "noo." Begin on a moderately low pitch, such as E, and move down by semitones. This exercise allows the singers to concentrate on basic vowel unification and tuning.

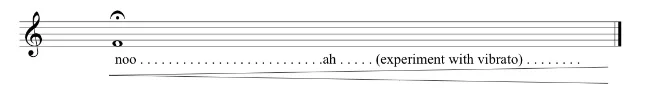

2. A variation of Exercise 1 is to sing through a series of vowels (generally moving from closed to open vowels). The singers should be asked to concentrate on maintaining their unison while progressing through successive vowel shapes. As they sing the more open vowels, they should be cautioned to avoid a) allowing the dynamic to suddenly become louder or b) allowing the pitch to drop.

Divisi Textures

3. Beginning with a unison, two then three then four pitches are sung on "loo" or "noo," creating a whole tone cluster. Singers may also sing "nee" or "naw," or move from "nee" to "aw." This exercise is also useful for revealing balance issues in two-, three-, and four-part divisi textures: the dissonance created by the cluster pitches shows, more readily than consonant intervals, whether one voice part is overbalancing the others.

Intonation

Exercises 4 through 7 are especially useful in establishing disciplines in the area of intonation. Though Robert Shaw would jokingly admit that altering a pitch one-sixteenth of a semitone at a time was likely not possible, hissingers would eventually learn to move gradually up (or down) by extremely small degrees—and maintain a unison throughout. (Note: with a mixed chorus, octave unisons should be maintained between the sopranos/tenors and altos/basses even as they negotiate the series of subtly-changing pitches).

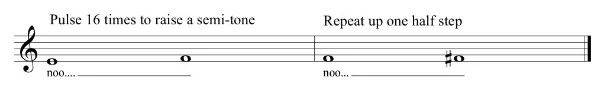

4. Beginning on a moderately low pitch such as E, move up one semitone in 16 pulsed unison pitches (effectively dividing the semitone into 16 separate notes, with each sung almost imperceptibly higher than the last). More intensive ear training can also be accomplished by separating the upper and lower voices by a minor third while they simultaneously perform this exercise.

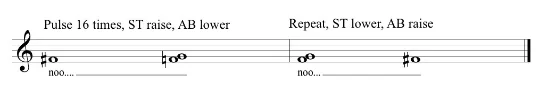

5. A variation of Exercise 4: starting on a unison, sopranos and tenors ascend one semitone while altos and basses descend one semitone, ending a whole tone apart.

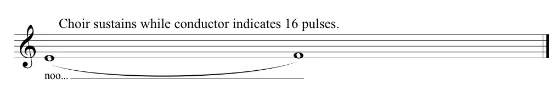

6. Another variation: sing Exercises 4 or 5 as a 16-beat sustained, unpulsed glissando.

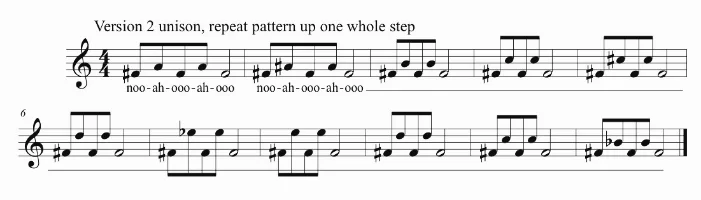

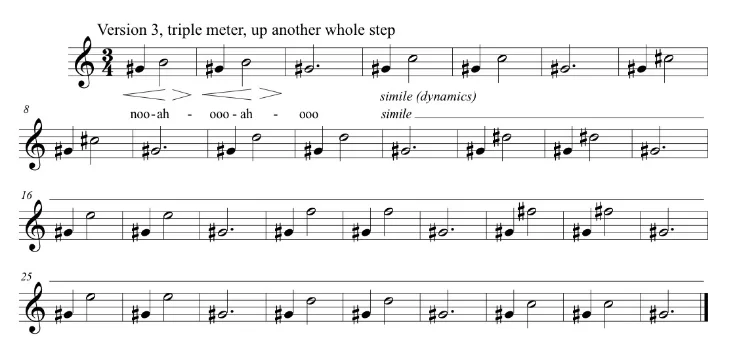

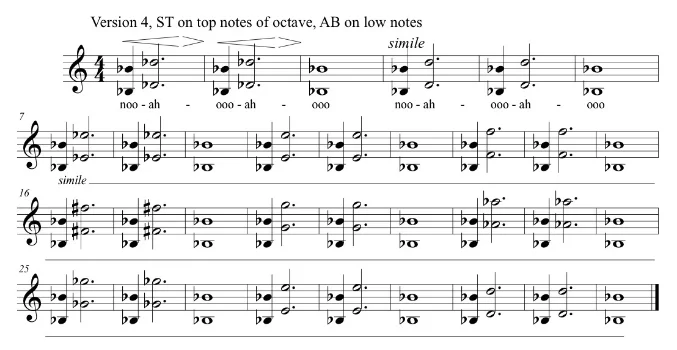

7. "Noo-ah" exercise. This is effective not only for developing the ears and brains in matters of intonation, but also for achieving unanimity of line through and between vocal registers. Singers should be asked to control the vowel shape and dynamic when moving from the "oo" to the "ah" vowel, so that the “ah” vowel doesn’t "pop out” suddenly. Singers who tend to carry too much weight from lower to upper registers will eventually learn to maintain a more consistent tone color as they sing larger intervals in higher registers. According to Norman Mackenzie, Shaw's long-time associate, the exercise ascends by semitones and descends by whole tones (concluding with the major 3rd relationship) for several reasons:

- To reinforce ear-training and attentiveness by using different intervals for ascending and descending; .

- To find more easily the next starting pitch/interval (because of the harmonic relationship);

- And as Shaw said with tongue in cheek, "to make the exercise somewhat shorter."

Note: Version 4 (in common, or 4/4 time) should be sung with tenors doubling sopranos an octave lower and basses similarly doubling altos .

Changes in Acoustics

Exercises 8, 9, 10 and 11 challenge singers to maintain correct intonation while constantly changing their immediate acoustic surrounding. For instance, when a singer turns in a circle while standing, he or she will be singing into ever-changing reflective or absorptive surfaces, forcing him or her to listen acutely in order to maintain a consistent pitch. A similar result may be achieved by asking singers to face the nearest wall of the shell (or room). In both instances, ears and minds are forced to make minute, instantaneous adjustments in order to maintain accurate pitch, tone color, and balance. Shaw maintained that this was the fastest way for singers to become accustomed to new acoustical environments.

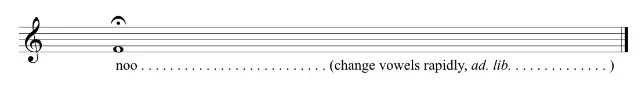

8. Beginning with a unison pitch on "noo" or "nee," change vowels rapidly ad lib while each singer slowly turns 360 degrees.

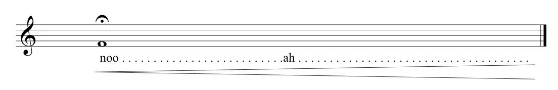

9. Move from "noo" to "ah" while simultaneously making a crescendo from a soft to a full dynamic. Then repeat the same with each singer facing the nearest wall. A variation is for each singer to turn 360 degrees while making the crescendo.

10. Another variation of Exercises 8 and 9 is to use whole tone clusters or minor thirds (with basses doubling altos and tenors doubling sopranos.)

11. Yet another variation of Exercise 9 is to add excessive vibrato once the dynamic level reaches forte, thereby distorting the pitch. Then repeat the exercise and add just enough vibrato to warm the pitch. Since this particular exercise is intended to develop an awareness of tonal consistency, singers should not be asked to turn 360 degrees. Rather, they should face forward so that they can maintain a consistent acoustical surrounding.

Tone Color

Exercises 12 and 13 are useful in developing an awareness of the variety of tone colors available to the choral ensemble. Note: a minor-third or whole-tone cluster may be used in place of a unison pitch.

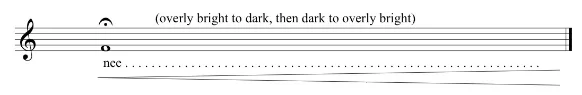

12. Begin with unison pitch on "nee" with an overly bright vowel. Crescendo and darken the vowel. Repeat the exercise, beginning with a tone that is too dark, gradually brightening the vowel during the crescendo.

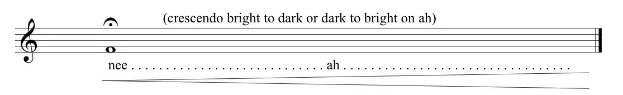

13. A variation of Exercise 12 is to begin dark and as the choir grows louder and brightens the vowel, open to "ah" while continuing the crescendo.

Dynamics

14. Measuring crescendos and diminuendos. This exercise is crucial to developing an ensemble's awareness of its own dynamic palette. If a chorus can establish levels of dynamic intensity as an isolated exercise, it will be more adept at achieving a wide spectrum of dynamic contrast when singing actual music.

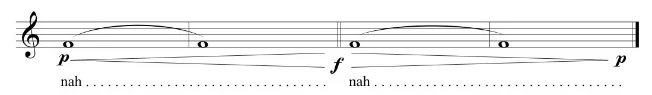

On a unison pitch, using the syllable, "nah," crescendo from piano to forte over a period of eight beats. Then, begin forte and decrescendo to piano for eight beats.

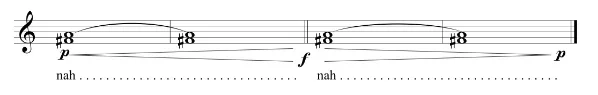

15. Instead of a unison pitch as in 14, use a minor third (with basses doubling altos and tenors doubling sopranos) or any combination of more than one pitch.

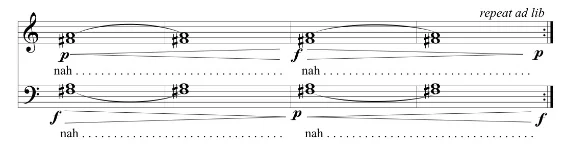

16. Using either a unison pitch, or more than one pitch, sopranos and altos begin forte, while tenors and basses begin piano. The chorus then sings simultaneous alternating eight-beat crescendos and decrescendos (depending upon the beginning dynamic), and repeats the process ad lib.

Robert Shaw believed that the well-trained amateur or volunteer chorus could equal a professional orchestra in quality of performance. But he maintained that attempting to master everything at once—text, rhythm, intonation, dynamics, unanimity of tone, etc.—would lead to a confused and imprecise result whereby the music could not be performed to its full potential. Skills were therefore to be taught and mastered one element at a time while continually refreshing those previously learned. Shaw’s warm-up techniques were a major element of his approach to choral preparation, with an expectation that his singers would ultimately assume personal responsibility for their own musical discipline. As choral directors, we should expect no less of ourselves and our singers.

This article was adapted from a longer version which first appeared in 2003 on the website of the Association of British Choral Directors (http://www.abcd.org.uk/). The author would like to thank the following for their input into this project: Thomas Shaw, Robert Shaw's son; Nola Frink, former administrative assistant to Robert Shaw; Norman Mackenzie, former musical assistant to Robert Shaw and currently the director of choruses for the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra; Ann Howard Jones of Boston University; Susan Brumfield of Texas Tech University; Thomas Hughes of Texas Tech University; John Dickson; and the 2003 Texas Tech University Choir.